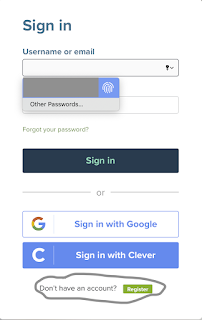

Checkology: The purpose of this post is to provide a quick overview of all Checkology lessons to aid school librarians and teachers in selecting lessons for students. Each lesson contains videos, quizzes to build understanding, and opportunities for written responses students can submit. Go to Checkology and login with your single sign-on or set up an account to be able to access the links from here. Each lesson image links to that lesson. After each lesson summary, I recommend the amount of time the lesson would take to complete in class and the courses in which the lesson would be useful. Finally, there are links to any available Checkology Practice and Extend Exercises or Challenges.

Checkology’s lessons and other resources show you how to navigate today’s challenging information landscape. You will learn how to identify credible information, seek out reliable sources, and apply critical thinking skills to separate fact-based content from falsehoods. The lessons take students through a series of explanations by journalists and activities that to reenforce the explanations.

1. What is News?

What Is News? defines the four litmus tests journalists apply in determining what is newsworthy: timeliness, importance, interest, uniqueness. Paul Saltzman from the Chicago Sun-Times guides students through activities in which the select which story is newsworthy, identify why a story is newsworthy, use sliders to rate a story's timeliness, importance, interest, uniqueness, and ultimately to rank stories in order of newsworthiness.

This lesson should take one class period for high schoolers and possibly two for middle school students. It would be relevant in journalism and media literacy lessons.

This lesson has TWO PRACTICE AND EXTEND EXERCISES

2. The First Amendment

The First Amendment Sam Chaltain, writer, filmmaker, and former high school teacher provides historical background about the First Amendment and the five freedoms. Students learn how the First Amendment protects them in their everyday lives, the limits to their rights, and how the five freedoms work together to protect you, the four main limitations to the freedom.

Chaltain introduces each of the following Supreme Court cases. Students are given the opportunity to read about, and dig deeper with additional links, predict the outcome of the case, and write their own written response to each of the Supreme Court's opinions.

- West Virginia State Board of Education et al. v. Barnette et al. (1943) (Pledge of Allegiance)

- Tinker et al. v. Des Moines Independent Community School District et al. (1969) (Student Protests)

- New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964) (Defamation without malice)

- Hazelwood School District et al. v. Kuhlmeier et al. (1988) (Censoring controversial articles in a high school newspaper or "school-sponsored" speech)

- Flag Burning

- Reno, Attorney General of the United States, et al. v. American Civil Liberties Union et al. (1997) (Censoring Internet content)

This lesson could take 3 class periods. Students can advance through the material without completing all of it. You could jigsaw the cases and ask students to provide "slug" responses in order to advance through the cases that are not theirs. It would be relevant in journalism, American history, and Government classes.

This lesson has one PRACTICE AND EXTEND CHALLENGE

3.Introduction to Algorithims

Nicco Mele, Director, Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government leads students to understand how personalization personalization algorithms affect search results. Students use sliders to view the difference between searches performed with personalization and without it and determine the benefits and drawbacks of personalization algorithms. Mele briefly discusses how students can click the like button on reliable, informative posts from a variety of perspectives to escape the filter bubble. This is not a deep philosophical dive into the ethics of search engine algorithms but rather a basic, comprehensible introduction to their existence.

This should take less than one class period and could be used with an additional activity. This is relevant to media literacy and computer programming courses.

4. Practicing Quality Journalism

Enrique Acevedo, Univision Anchor, shows how to identify quality journalism to help separate fact from fiction. In this engaging adventure, students are put on the scene of an accident and asked to play the role of a new reporter gathering and verifying information along the way in order to learn what it takes to follow the standards of quality journalism. Students read a brief description of the Seven Standards of Quality Journalism. This is really a fun adventure in which students listen to witnesses, voicemails from city officials, analyze a variety of official documents and social media posts and monitor their adherence to the Seven Standards along the way. Finally, they are prompted to select appropriate headline, first sentence, appropriate image, and ensuing paragraphs based on their adherence to the Seven Standards.

This should take high school students 2-3 days, depending on their level. I would think it would be more like 4 days for middle school students. This is an excellent lesson for journalism students and to help students notice the hallmarks of reliable journalism in a media literacy lesson. Fun lesson!

This lesson also appears in Spanish! It would be a fun lesson to do in Spanish foreign language in starting at Spanish II for Spanish speakers or Spanish III for non-native speakers.

5. Be the Editor

In this lesson, students use the big four elements they learned in lesson one– timeliness, importance, interest, uniqueness– to decide what makes it to press. Students are given a list of 18 headlines. They must select 5 they deem worthy of publication and then prioritize their importance. They provide written justifications for their choices and examine "reader comments" to see if readers agree with their selections.

This fits in a journalism class. It could possibly be in English classes to reenforce the idea of considering one's audience. This would probably take 1 period if the students are really careful in their selections. It would take longer and might be better if students worked in small groups to make editorial decisions together.

6. Citizen Watchdogs

Temerra Griffin of BuzzFeed News talks about how everyday citizens can hold the government, corporations, and even the news media accountable by sharing images, film, and information through the use of cell phone video and social media.

The lesson presents each of the following events, provides links to more information about each event, and prompts students to write responses to questions to process what they've watched and read.

- The Rodney King beating.

- Dr. Jeffrey Wigand, tobacco industry whistle blower

- The beating of Khaled Mohamed Saeed by Egyptian police.

- The police murder of Philando Castille

- Wikileaks

- How people can use Twitter or email to comment on the accuracy and bias in journalists work.

This lesson has ONE PRACTICE AND EXTEND CHALLENGE:

7. Branded Content

Emily Withrow, Assistant Professor, Northwestern University. In this episode, Withrow helps students differentiate between news and branded content, which is advertising that aspires to emulate news reporting in its presentation. She explains that with the advent of the internet consumers no longer needed to pay for news subscriptions and advertisers had many new and less expensive ways to advertise. At the same time that news organizations most needed revenue, advertisers least needed news organizations. Consequently, newspapers and magazines began allowing paid content to appear that was deceptively similar to news in order to entice paying advertisers.

In the activities in this module, students are exposed to a wide range of branded content, hoax ads, transparent ads, and legitimate content to help them accurately identify each despite their subtle differences. Students are asked to rate how ethical ads are (see image below) and can participate in advanced challenge activities.

This interesting and thought-provoking piece fits in with journalism, media literacy, film production, and English classes. You could easily ask students to produce ads in both film production and English classes to increase their awareness of these techniques. This lesson could be done in a couple of days. It could be extended into a short unit study as well.

This lesson has THREE PRACTICE AND EXTEND EXERCISES

This lesson has ONE PRACTICE AND EXTEND CHALLENGE:

8. InfoZones

- Entertainment - To entertain

- Advertisement - To sell

- Opinion - To persuade

- Propaganda - To provoke

- Raw information - To document

- News - To inform

This clear presentation will organize students thinking and help them to be more news savvy. It would work well in journalism, media literacy, English, and social studies classes. It should take 1-2 days, but could be easily expanded if students are producing their own content and presenting it.

This lesson has FIVE PRACTICE AND EXTEND EXERCISES:

This lesson has ONE PRACTICE AND EXTEND CHALLENGE:

9. Press Freedoms Around the World

This module provides an overview of press freedom, or the degree of legal and/or constitutional protections that journalists have in doing their jobs, and whether they are able to report freely without fear of retaliation. Press freedom in counties is ranked on the following scales: ownership of media, judicial protection, treatment of journalists, legal protection. Students are given an opportunity to enter the Checkology virtual classroom and look at countries around the work to evaluate their press freedom.

This overview would work well in journalism, media literacy, and social studies classes. It should take 1 class period, but there are many ways you might want to extend this.

10. Democracy's Watchdog

Wesley Lowery, Journalist investigative reporter on law enforcement, justice, and injustice elucidates the important role the watchdog journalism and free press have played in American democracy. First amendment protects journalists from retaliation.

Starts with Sway presentation of Notable Investigative Journalism Cases Throughout History that briefly introduces each of the following cases shows how watchdog journalism exposes threats to all of us and has resulted in societal improvements. The five with asterisks are covered in depth throughout the module with engaging text, video, timelines and links to additional information as well as debriefs.

- Ten Days in a Madhouse, Nelly Bly 1887***

- Ida B. Wells documents lynching, 1890s ***

- Moses Newson covers civil rights movement 1950s-60s.

- Silent Spring (Rachel Carson) 1962

- My Lai massacre 1969***

- The Pentagon Papers 1971

- Watergate 1972-74

- "Linel Geter's in Jail" 1983

- (Chicago) "City Council, The Spoils of Power" 1987

- "Tainted Cash or Easy Money" police stops/racial profiling 1992

- Tribal Housing: From Deregulation to Disgrace -1996

- Spotlight Investigation: Abuse in the Catholic Church 2002

- Surveillance of Muslim Communities 2011

- The NSA's global surveillance program 2013

- "Medicare Unmakes" 2014

- "Product of Mexico" 2014***

- Why did the U.S. Lock up these women with men? 2014

- "Fatal Force" (creating a database of police shootings)2015***

- Exxon and Climate Change 2015

- The Panama Papers 2016

- "Out of Balance" (Larry Nassar) 2016

- Harvey Weinstein 2017

This lesson has one PRACTICE AND EXTEND CHALLENGE

11. Arguments and Evidence

Kimberly Strassel, Opinion Writer, Wall Street Journal

In this lesson Strassel helps students distinguish between evidence and opinion pieces with no evidence or based on logical fallacies. The logical fallacies reviewed here are:

- Ad hominem (this is the only one that is clearly defined; questions are used to teach students to deduce knowledge of the remaining terms rather than to test their learning of them)

- False Equivalence

- Slippery Slope

- False Dilemma

- Straw man

The lesson uses a fictionalized scenario about a student who photograph and posts and image from s a high stakes test. Evidence for supporting arguments about whether or not to ban cell phones in school is contrasted with arguments based on logical fallacies.

This is a shorter lesson that could be used to introduce logical fallacies in English, A.P. Language, A.P. Seminar, journalism, digital citizenship, and media literacy lessons. It should take one class period.

This lesson has TWO PRACTICE AND EXTEND LESSONS:

12. Misinformation

Claire, Wardle, Ph.D. Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government

This lesson looks at the following five types of misinformation and gives students an opportunity to apply the definitions of each one with activities:

- Satire (this is the only one that is clearly defined; questions are used to teach students to deduce knowledge of the remaining terms rather than to test their learning of them)

- False Content

- Imposter Content

- Manipulated Content

- Fabricated Content

It also addresses the questions:

- What is misinformation?

- Why should we care?

- How can we fight back?

Wardle makes an impassioned case for the dire consequences of misinformation and disinformation. This lesson provides students with strong motivation to be responsible and proactive digital citizens.

This lesson could be completed in one class period. It fits in with any lessons about digital citizenship, social studies, propaganda, etc.

This lesson has ONE FOLLOW-UP LESSON

13. Understanding Bias

In this lesson, students are asked to consider the bias of others and themselves. Lakshmanan poses the following questions to guide the lesson.

How do our own biases affect our perception of everything?

What are some different types of bias?

What are the ways they occur?

Who gets to decide if something is biased?

She introduced the journalists code of ethics.

- Seek the truth

- Minimize harm

- Act independently

- Be accountable

Then students are given an opportunity to build knowledge of first the following types of biases and the the forms of biases pictured below. Students are provided with a series of scenarios to classify according to type first and form second in order to deduce an understanding of each one.

There is a wealth of information for aspiring journalists included in this module. Students are asked to understand that thinking you see bias is just the beginning and to remember that not all journalism is meant to be neutral.

I would allocate 2-3 periods on this at least.There is a lot of information here, and it's a must do for any journalism class. It would also work well for social studies students examining sources, media literacy lessons, and English classes.

14. Conspiratorial Thinking

Renee DiResta, Technical Research Manager, Stanford Internet Observatory

This is an excellent two-part lesson that provides information and ample opportunities for student to process it.

Part One defines conspiracy theories, what attracts people to them, and distinguishes between real conspiracies and conspiracy theories.

Part Two explains the psychological and cognitive factors that cause people to get sucked into believing conspiracy theories.

Part One:

Students are provided the following definition of a conspiracy theory and given the opportunity to distinguish investigative reporting from conspiracy theory:

An unfounded explanation of an event or situation that blames the secretive work of sinister of sinister, powerful people the includes a company, a government, or even one person. It is based based on faulty logic, bad evidence or no evidence.

It provides the" different ways conspiracy theories appeal to people

- Conspiracy theories give people something or someone to blame as they cope with fears, anxieties and pain.

- Conspiracy theories offer simple explanations for complicated events and phenomena.

- Conspiracy theories prove people with a sense of belonging, support, and comfort. [Us (people who believe it) vs. them (people who can't see the conspiracy or who are responsible for the conspiracy)]. Confirmation bias and the echo chamber are in full effect here.

- Scope -real ones are usually much smaller

- Number of people involved (fewer in real ones)

- Records (some emerge or can be obtained through FoIA

- Witnesses and whistleblowers.

Students are given many opportunities such as the one in the image below to process their knowledge:

This section shows how motivated thinking and cognitive biases create the perfect recipe for conspiratorial thinking.

Motivations for believing conspiracy theories:

- They offer a perpetrator when there is none

- Epistemic motivation (we want to make sense out of things and have a stable narrative)

- Existential motivation (need to feel safe, secure, and in control)

Conspiracy theories appeal to cognitive biases, which are common errors in the way we take in and frame information to justify the cause and effect relationship of the conspiracy

Cognitive biases at play with conspiratorial thinking:

- Proportionality bias (a huge tragedy-JFK's murder must have a huge cause)

- Intentionality bias (randomness is scarier to contemplate than intentional acts)

- Confirmation bias then comes into play when people begin to accept claims that reinforce their existing beliefs and dismiss claims that don't. Search algorithms reinforce existing beliefs as well.

Cognitive dissonance also plays a role in making people vulnerable to conspiratorial thinking. Cognitive dissonance here is defined as:

The mental discomfort of having a deeply held belief challenged and responding by seeking out any information that either supports the belief or discredits contradictory information to ease discomfort, even if that information is false.

Three key elements contribute to conspiratorial thinking:

- Motivated reasoning

- Institutional cynicism (Ironically, when people become cynical about all official agencies and expert entities, they begin relying solely on the least reliable sources that have accountability to fairness, transparency, and accuracy.)

- Illusory pattern perception (perception of meaningful patterns in unrelated facts or events - a fanciful version of this is seeing animals in clouds or a rabbit on the moon)

I would allocate 3-4 class periods for this if it is all to be done in class. It is an excellent break down of the issue. It would work well in science classes, media literacy, English, and social studies. You could possibly cover this in computer programming to show how search algorithms play a role in exacerbating conspiratorial thinking.

Impressive! I have a few of the new one I need to do.

ReplyDeleteThe Conspiracy Thinking ones are really excellent!

DeleteThis is great! Thank you - will you keep updating this page as new modules/lessons are added to Checkology?

ReplyDelete